Retinal detachment

Information for patients from the Ophthalmology Department

What is the retina?

-1729237697.jpg)

The retina is a fine sheet of nerve tissue lining the inside of your eye. Imagine your eye as a camera, with the retina being the film. When rays of light enter your eye they are focused on to the retina by the lens.

The retina produces a picture, which is sent along the optic nerve for your brain to interpret. In much the same way that we develop the film in a camera to produce pictures.

The retina is normally attached to the coating of the eye ball at the back of the eye, similar to wallpaper attached to the wall.

What is a retinal detachment?

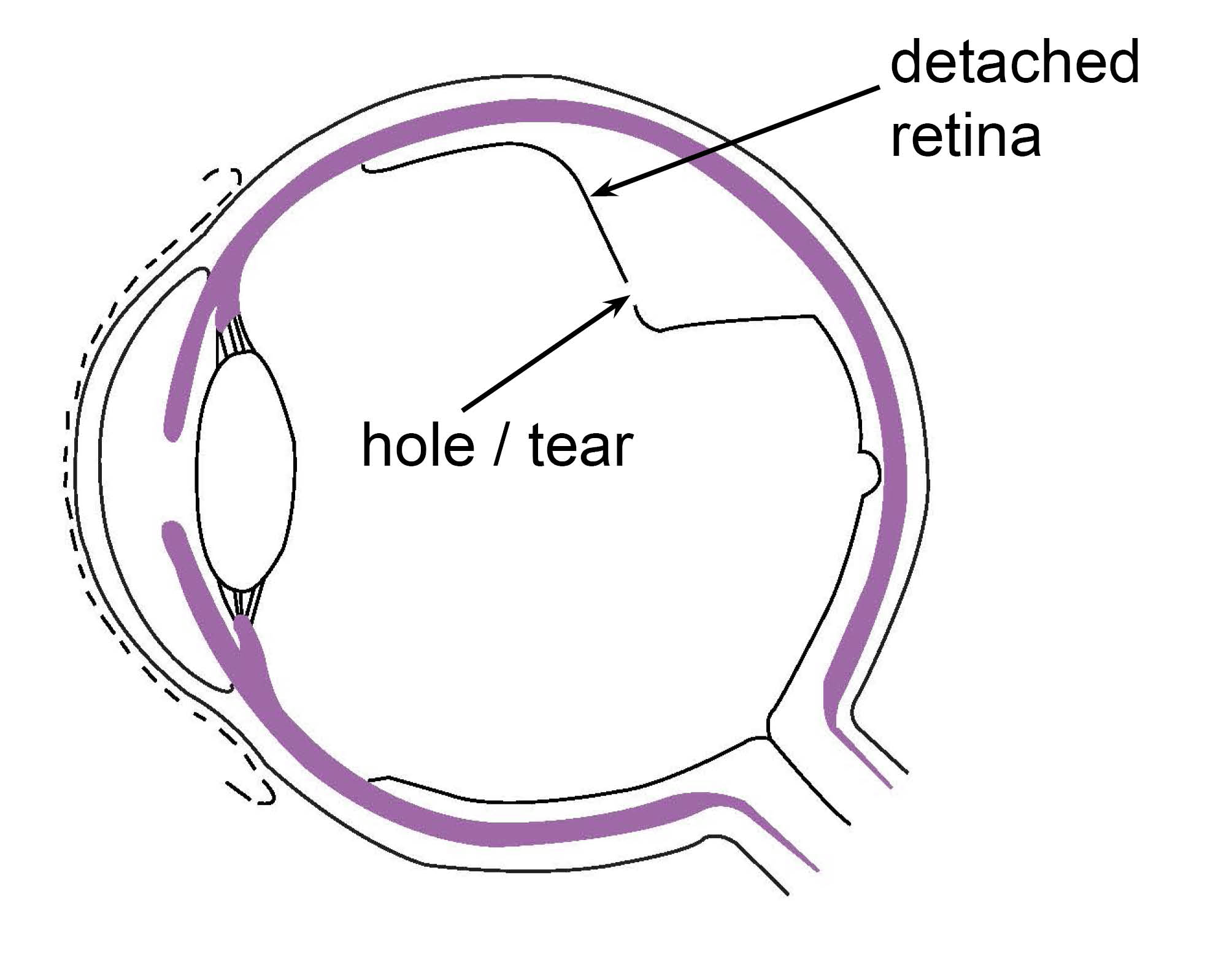

Retinal detachments often develop in eyes where the retina has been weakened by a hole or a tear. A hole or tear in the retina allows fluid from the vitreous cavity (area that is filled by vitreous gel) to leak in.

As the fluid passes through the tear, it may detach the retina from the back of the eye, rather like wallpaper peeling off a damp wall.

When detached, the retina cannot compose a clear picture from the incoming rays and your vision becomes blurred and dim. If left untreated, the retinal nerve tissue dies and you will loose vision.

Why does a retina tear?

As we get older, or because of any of the conditions listed on the next page, the vitreous gel begins to degenerate and shrink, pulling away from its attachment to the retina. Usually it separates from the retina without causing any problems, but in one in 10 cases the vitreous (a transparent jelly like substance filling the back of the eye from lens to retina) pulls hard enough, or the retina is sufficiently fragile for the retina to become torn in one or more places.

The retinal tissue can also weaken on its own, and tear over time. For more information, please ask a member of staff for a copy of the Trust’s Retinal tear leaflet.

What increases the risk of a retinal detachment?

You are at a higher risk of a retinal detachment if you:

are myopic (short sighted)

have diabetes or Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

have had a previous retinal detachment in your other eye

have a family history of retinal detachment

have weak areas in your retina (that can be seen by your ophthalmologist (eye doctor)); or

have had a cataract, or other eye surgery or trauma.

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptom is a shadow spreading across the vision of one eye (rather like a curtain). You may also see bright flashes of light and / or showers of dark spots called floaters. These symptoms are never painful.

Many people have flashes or floaters, but these are not necessarily a cause for alarm. However, if they are severe or have appeared suddenly and seem to be getting worse and you are losing vision, then you should ask for medical advice. Quick treatment can often minimise the damage to your eye.

How is it diagnosed?

An ophthalmologist can usually see a retinal tear or detachment by examining your retina through a magnifying lamp, while your pupil is dilated.

Whilst this is often part of a routine eye examination, this condition should be treated as an emergency so you should not wait until your next appointment to have your eye examined. Please contact your GP or optometrist for an urgent appointment on the same day. If concerned, your GP or optometrist will organise an emergency appointment with the Eye Casualty Department on the Rotary Ward at the William Harvey Hospital Ashford.

What is the treatment?

Retinal tear: if retinal tears are treated early enough, a detachment can be prevented. This can be done by cryotherapy (freezing) or laser treatment.

Retinal detachment: the only way to treat a retinal detachment is by having an operation to find the holes or tears and to seal them.

There are a number of treatments for retinal detachment. Your doctor will discuss the following options with you.

Vitrectomy (the internal approach)

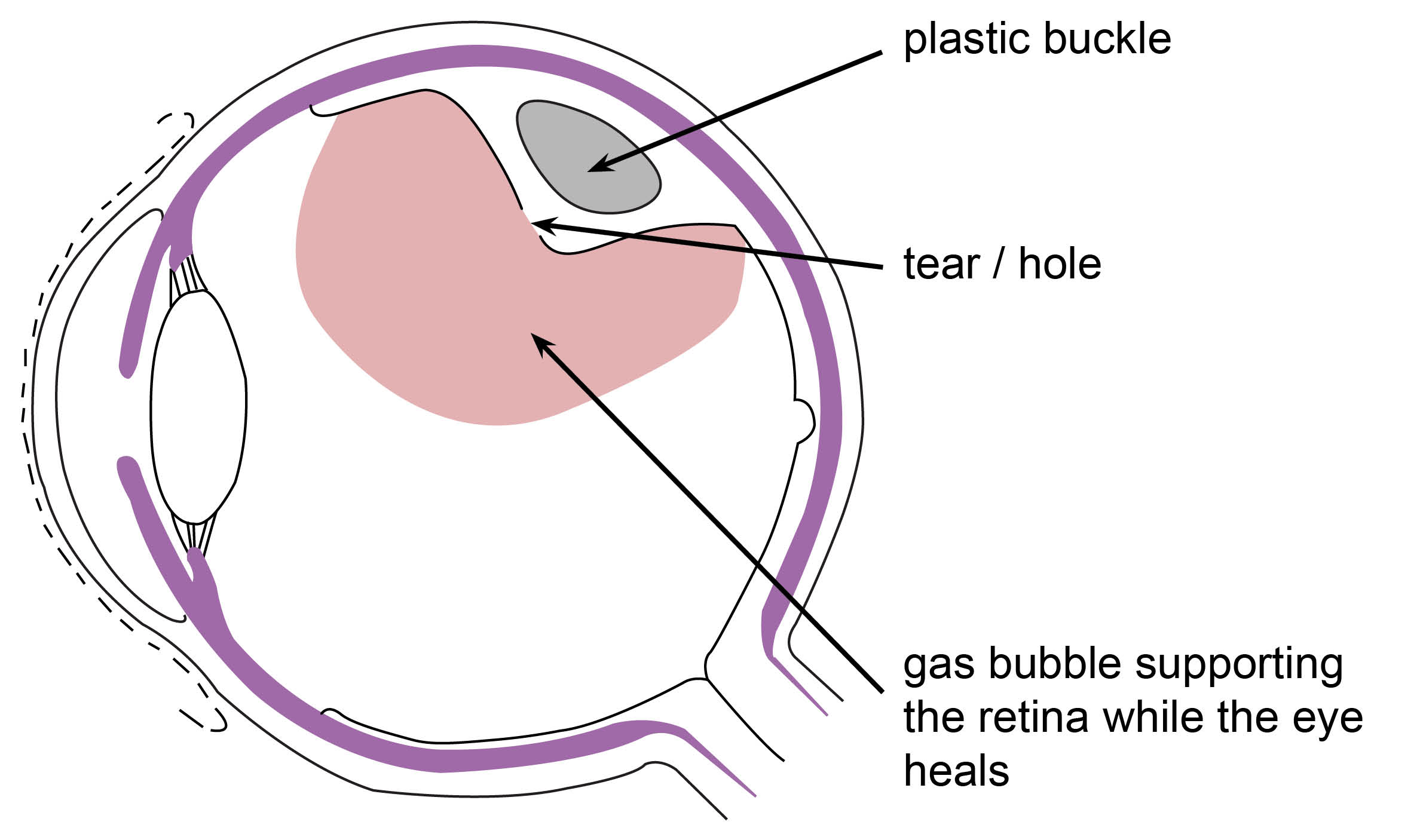

Sometimes the jelly inside your eye (vitreous) has to be removed. Fine instruments are placed through small holes in the white of your eye and the jelly inside is cut up and sucked out. The breaks will be revealed and treated either with laser or cryotherapy. A gas bubble is then injected in to your eye, to support the retina while your eye heals.

Scleral buckling (the external approach)

Sometimes we can seal the hole that has caused the detachment by stitching a piece of plastic (called a buckle) over the outside of your eye after cryotherapy. The buckle creates a dent inside your eye ball allowing the hole inside to close.

You will feel some discomfort following surgery but this will calm down.

Is gas the only material that can be used?

Sometimes silicone oil is inserted in to the eye instead of gas. The oil (a clear colourless fluid) is injected in to the eye and holds the retina in place until it reattaches to the wall. The oil is usually surgically removed within a year of surgery.

The procedure takes approximately 30 minutes. The oil can be left in place in some cases where further surgery would normally be needed. Silicone oil can cause glaucoma or cataracts in some cases.

Which surgery will be best for me?

The results of surgery have similar rates of reattachment, although sometimes further surgery may be needed. Your surgeon will decide the best treatment for you. This is based on a number of factors, including the type of detachment that you have.

How successful is the surgery?

The chance of success depends on how bad your retinal detachment is. Overall the success rate of the first operation is around 85 out of 100 patients (85%). This means that some people will need more than one operation.

If your retina has produced scar tissue the chances of success are reduced. The amount of scar tissue is known before your surgery as it defines how bad your retinal detachment is. Some patients will obtain good vision; others will lose vision even if their retina is reattached.

There is a 7% chance of losing all of your vision in your affected eye despite surgery.

What is the recovery period?

Improvement in your vision happens over several weeks, but can take over a year to reach full recovery.

What are the complications?

The surgery is difficult and complications can happen. These include infection, bleeding, cataract, glaucoma, inflammation, wound problems, drooping eyelid, double vision, distortion, and blurred vision.

How much vision can I expect after a successful operation?

This depends on how much retina has detached and for how long.

The shadow caused by the detachment will usually disappear when the retina has been put back in place. If your ability to see fine detail has been damaged before your operation, it may not fully recover afterwards.

What happens if a detached retina is not put back in place?

Most people will lose all useful vision if no operation is carried out, or if the treatment is unsuccessful. However, further treatment is usually possible if it does not succeed the first time.

What happens after my surgery?

You may be asked to position your head in a certain way following your operation, to help with healing. There is a separate leaflet called Positioning (Posturing) following vitreoretinal eye surgery, which will explain this to you in detail. If you have not been asked to posture, you can get up and move around following your eye surgery.

You will be prescribed eye drops which you will need to use for several weeks.

Often you will need to change your glasses prescription following eye surgery. You should speak to your doctor about the best time to visit your optician.

You will be given a booklet called Discharge advice following eye surgery when you leave hospital. This lists a 24 hour emergency telephone number to contact should this be needed.

References

Patient Pictures. Ophthalmology Merck Sharp and Dohme Ltd, 2001

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Mardeno Patient Atlas. Ophthalmology 2003 to 2005. 1st edition.