Preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes (PPROM)

Information for women, birthing people and their families

If you are reading this leaflet it is possible that you or someone you know may have preterm pre labour rupture of membranes (PPROM), this leaflet will explain what that means.

What is preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes (PPROM)?

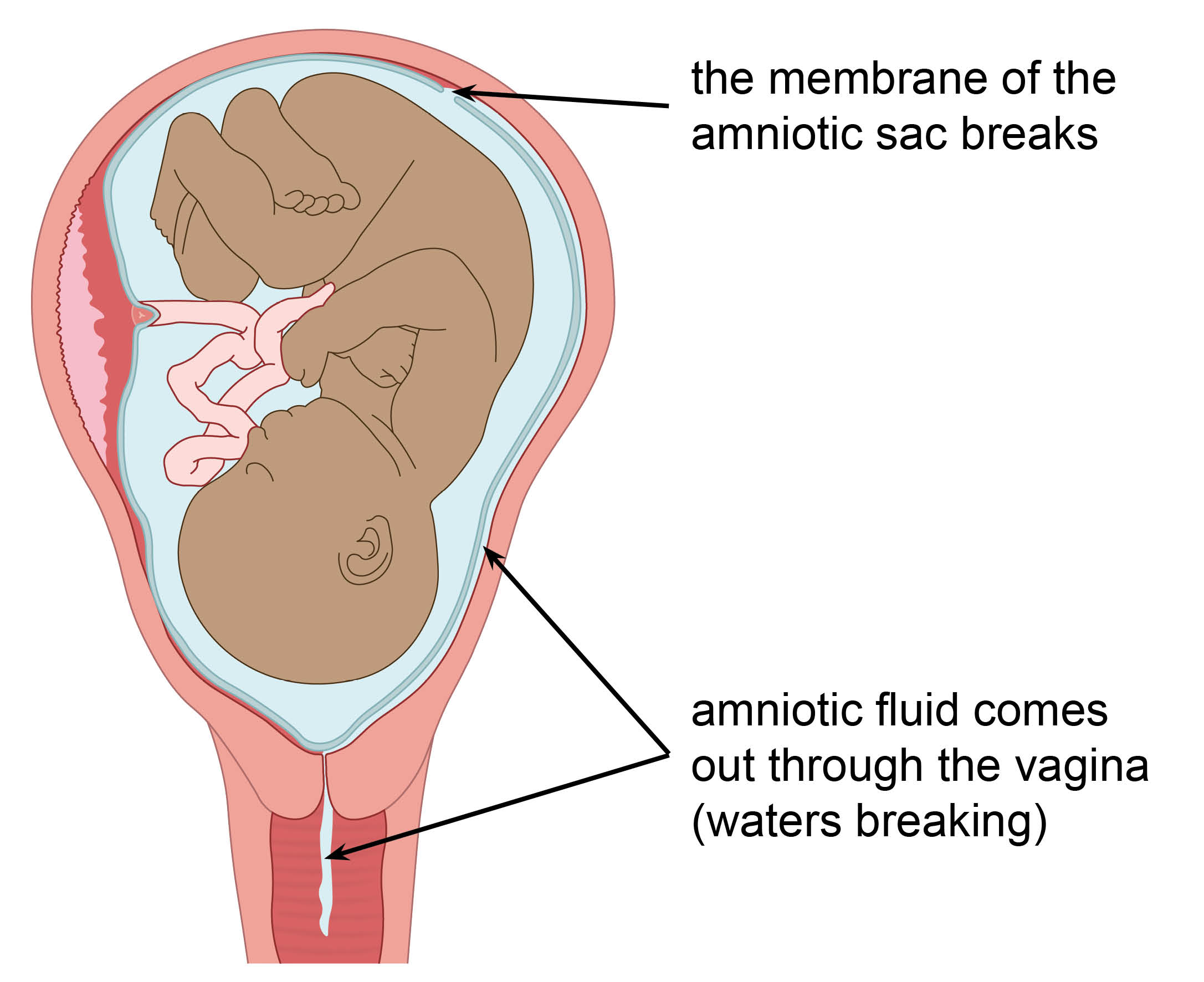

Your baby develops inside a bag of fluid called the amniotic sac. When your baby is ready to be born, the membrane of the amniotic sac breaks and the fluid comes out through your vagina. This is your waters breaking. It is also known as rupture of the membranes.

Normally your waters break shortly before or during labour. If your waters break before labour, at less than 37 weeks of pregnancy, this is known as preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes or PPROM.

If this happens, it can (but does not always) trigger early labour. If your waters break early, the risks and your treatment will depend on what stage of your pregnancy you are at.

Is PPROM common in pregnancy?

PPROM happens in about 3 in every 100 pregnancies.

What causes PPROM?

We do not always know why PPROM happens, but it may be caused by one of the following.

Infection.

Problems with your placenta, for example where the placenta does not develop properly or is damaged.

A blood clot develops behind the placenta or membranes.

You may have other risk factors if you:

have had a premature birth or PPROM before

have had any vaginal bleeding during your pregnancy

have had any direct trauma (injury) to your stomach

have had cervical surgery (such as a large loop excision transformation zone (LLETZ) procedure) or you have a short cervix

have had placental abruption before (the placenta does not develop properly or is damaged)

have extra fluid around your baby in the amniotic sac (known as polyhydramnios)

are pregnant with more than one baby.

It is important to remember that PPROM is not caused by anything you did or did not do in pregnancy.

How will I know if my waters have broken?

Your waters breaking may feel like a mild popping, followed by a trickle or gush of amniotic fluid that you cannot stop, unlike when you wee. The amount of amniotic fluid you lose may vary. You may not feel the actual ‘breaking’, and you only notice your waters have broken when you feel the trickle of water. It does not hurt when your waters break.

Amniotic fluid is clear and a pale colour. It may be a little pinkish if it contains some blood. You must call Maternity Triage or go to your nearest hospital if:

your waters are smelly or coloured a yellow, brown, or bright red; or

you are losing fresh blood.

This could mean that you and your baby need to be seen urgently.

What happens next?

If your waters have broken, you will usually be advised to stay in hospital where you and your baby will be closely monitored for signs of infection. This may be for a few days or it may be longer.

You will have your temperature, blood pressure, and pulse taken regularly, as well as blood tests to check for infection.

Your baby’s heart rate will also be monitored regularly.

You may be offered antibiotics to help reduce the chances of infection.

If your waters have not broken, you should be able to go home.

If you continue to leak amniotic fluid at home, you should contact the hospital immediately for a further check-up.

What could PPROM mean for me and my baby?

If your waters have broken early, your midwife or doctor will discuss with you what this could mean for your baby. This will depend on how many weeks pregnant you are when this happens and your individual circumstances.

Infection

The membranes (amniotic sac) form a protective barrier around your baby. After your membranes break, and amniotic fluid can leak out, there is a risk that you may develop an infection. This can cause you to go into labour early or cause you or your baby to develop sepsis (a life-threatening reaction to an infection).

The symptoms of infection include the following.

Feeling hot and clammy with shivering.

An unusual vaginal discharge, with an unpleasant smell.

A fast heart rate.

Pain in your lower stomach.

Feeling generally unwell.

Your baby’s heart rate may also be faster than normal. If there are signs that you have an infection, your baby may need to be born straight away. This is to try to prevent both you and your baby becoming more unwell.

PPROM and premature birth

About half of women with PPROM will go into labour within one week of their waters breaking. The further along you are in your pregnancy, the more likely this is to happen. PPROM is linked with 3 to 4 out of every 10 premature births.

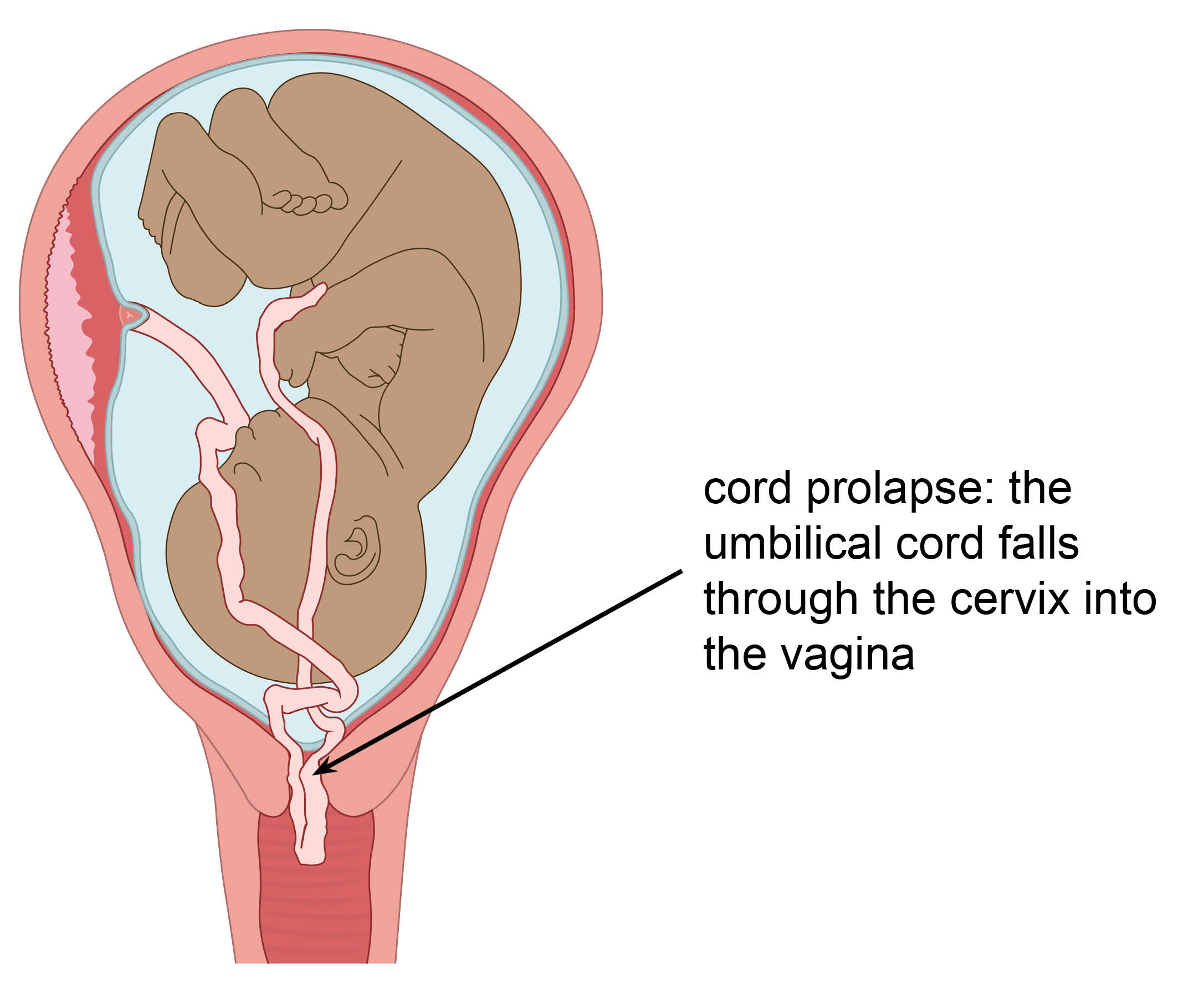

Cord prolapse

Cord prolapse is when the umbilical cord falls through your cervix in to your vagina. This is an emergency complication and can be life-threatening for your baby, but it is uncommon.

Pulmonary hypoplasia

This is when your baby’s lungs do not develop normally because they no longer have amniotic fluid around them. This is more common if your waters break very early on in your pregnancy (less than 24 weeks) when your baby’s lungs are still developing.

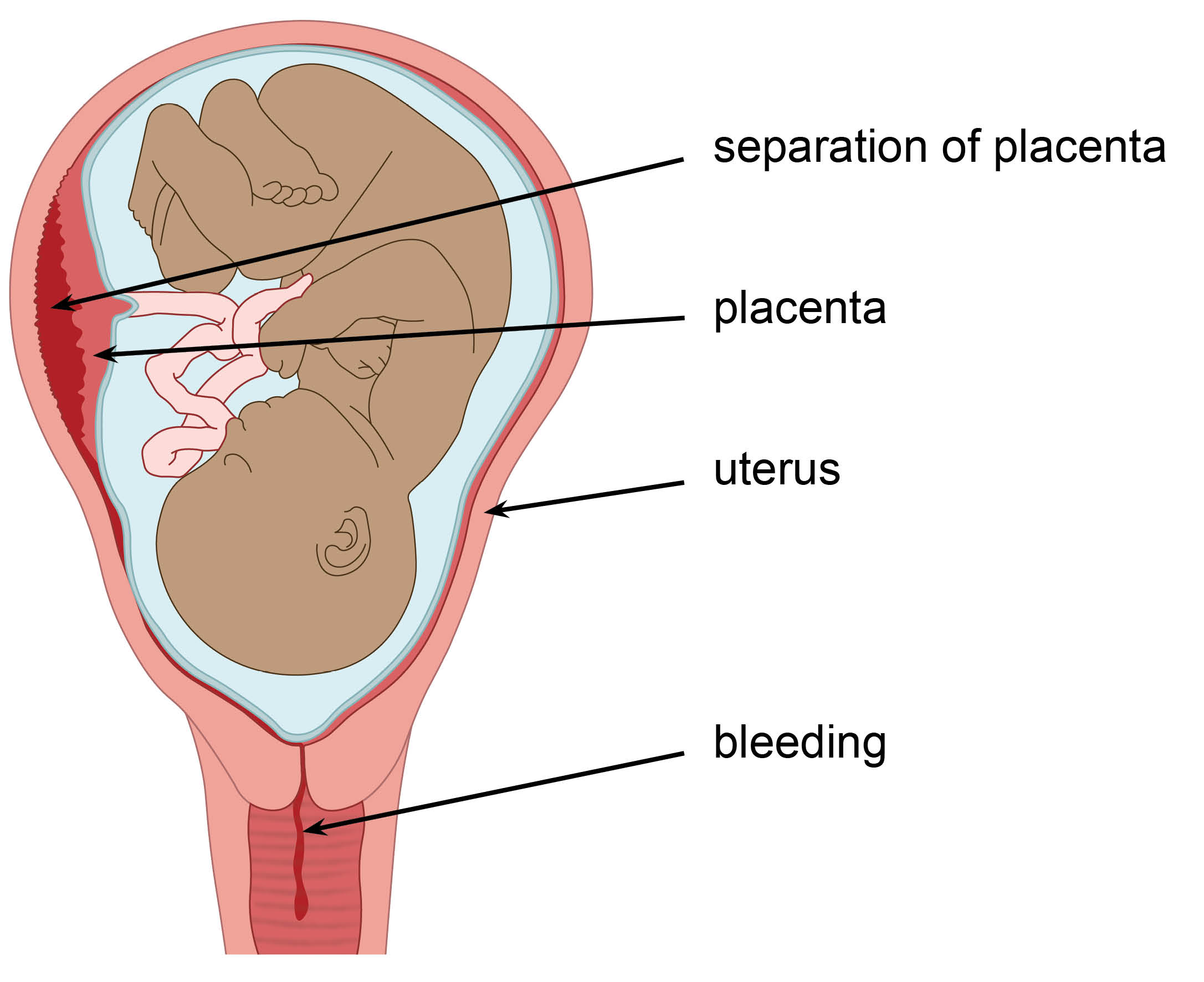

Placental abruption

This is when your placenta separates or starts to separate from your uterus. It can cause pain and heavy bleeding, it can be dangerous for both you and your baby. This is an emergency and you should seek medical attention immediately or call 999. It is important to note that sometimes there can be heavy bleeding with no pain.

Find out more about placental abruption on the Tommy’s web site.

-

Umbilical cord prolapse

Umbilical cord prolapse -

Placental abruption

Placental abruption

If you experience PPROM, sadly sometimes your baby may not survive. There is a higher risk of this happening if your waters break very early, if your baby is born very prematurely (under 24 weeks) or in some cases, following infection or cord prolapse.

Are there any treatments for PPROM?

It is not possible to ‘fix’ or heal membranes once they are broken, but you may be offered treatment to reduce the risks to your baby. This could include:

a short course of antibiotics to reduce the risk of an infection and delay labour

a course of steroid injections (corticosteroids) to help with your baby’s development and to reduce the chance of problems caused by being born prematurely

magnesium sulphate once you are in labour, which can reduce the risk of your baby developing cerebral palsy if they are born very premature.

If you do go into premature labour, you may be offered intravenous antibiotics (where the antibiotics are given through a needle straight into a vein) to reduce the risk of early-onset Group B Strep (GBS) infection. For more information, please read the leaflet Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnancy and newborn babies.

If you have any questions or concerns about the treatments listed above, please speak to your midwife or doctor.

Do I need to stay in hospital?

We usually advise you to stay in hospital for at least 48 hours after your membranes break, so we can monitor you and your baby’s wellbeing. You may be able to go home after that, if your doctor considers that you are not at risk of giving birth early and have no signs of infection.

Before being sent home, you will be given clear advice on how to take your pulse and temperature at home. You will probably be advised to avoid having sex during this time.

When should I ask for help if I go home?

Contact Maternity Triage, and return to the hospital immediately if you have any of the following.

Flu-like symptoms (feeling hot and shivery).

Bleeding from your vagina.

The leaking fluid becomes greenish or smelly.

Contractions or cramping pain.

Abdominal (stomach) or back pain.

You are worried that your baby’s movements have slowed down, stopped, or changed. Contact Maternity Triage immediately if this happens (see contact details at the end of this leaflet).

What follow-up should I have?

After PPROM you should have regular check-ups with a midwife or doctor, usually once or twice a week. These check-ups will be as well as your routine appointments with your midwife.

During these check-ups your baby’s heart rate will be monitored, your temperature, pulse, and blood pressure will be checked, and you will have blood tests to look for signs of infection. Your doctor will discuss with you an ongoing plan for your pregnancy, including regular ultrasound scans to check on your baby’s growth.

When is the right time to give birth?

If you and your baby are both well with no signs of infection, we may advise you to wait until 37 weeks to give birth. This is because it can reduce the risks linked with your baby being born prematurely.

If you are carrying the GBS bacteria, you may be advised to give birth from 34 weeks because of the risk of GBS infection for your baby. For more information, please read the leaflet Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnancy and newborn babies.

Your midwife or doctor will talk to you about what they think is best for you and your baby, and ask you what you want to do. Do not be afraid to ask as many questions as you need to in order to feel comfortable and able to make informed decisions about your care.

Will I be able to have a vaginal birth after PPROM?

A vaginal birth after PPROM is possible, but it depends on:

when you go into labour

the position your baby is lying; and

your own individual circumstances and choices.

Your midwife or doctor will discuss this with you.

Will I have PPROM again with a future pregnancy?

Possibly. Having PPROM or giving birth prematurely means that you are at an increased risk of having a preterm birth in any future pregnancies, but it does not mean that you definitely will.

You may be referred to the Preterm Birth Surveillance Clinic in your next pregnancy. For more information, please read the Preterm Birth Surveillance Clinic leaflet.

If you are not offered specialist care, you can ask for it. Remember that you can always talk to your midwife if you have any concerns about your care.

What if I have any concerns or questions when I return home?

Contact Maternity Triage on 01227 206737 for help and advice. They are available 24 / 7 and will be happy to answer any questions.