Operations for prolapse of the vaginal apex

Information for patients from the British Society of Urogynaecologists (BSUG)

This leaflet was written by members of the BSUG Governance Committee, paying particular reference to any relevant NICE Guidance.

This leaflet explains the following:

What a vaginal vault prolapse is.

What alternative treatments are available within our Trust.

The risks involved in surgery.

What operation we can offer.

What happens before, during and after surgery.

We hope this leaflet answers some of the questions you may have. If you have any further questions or concerns, please speak to a member of your healthcare team.

What is a prolapse of the vaginal apex?

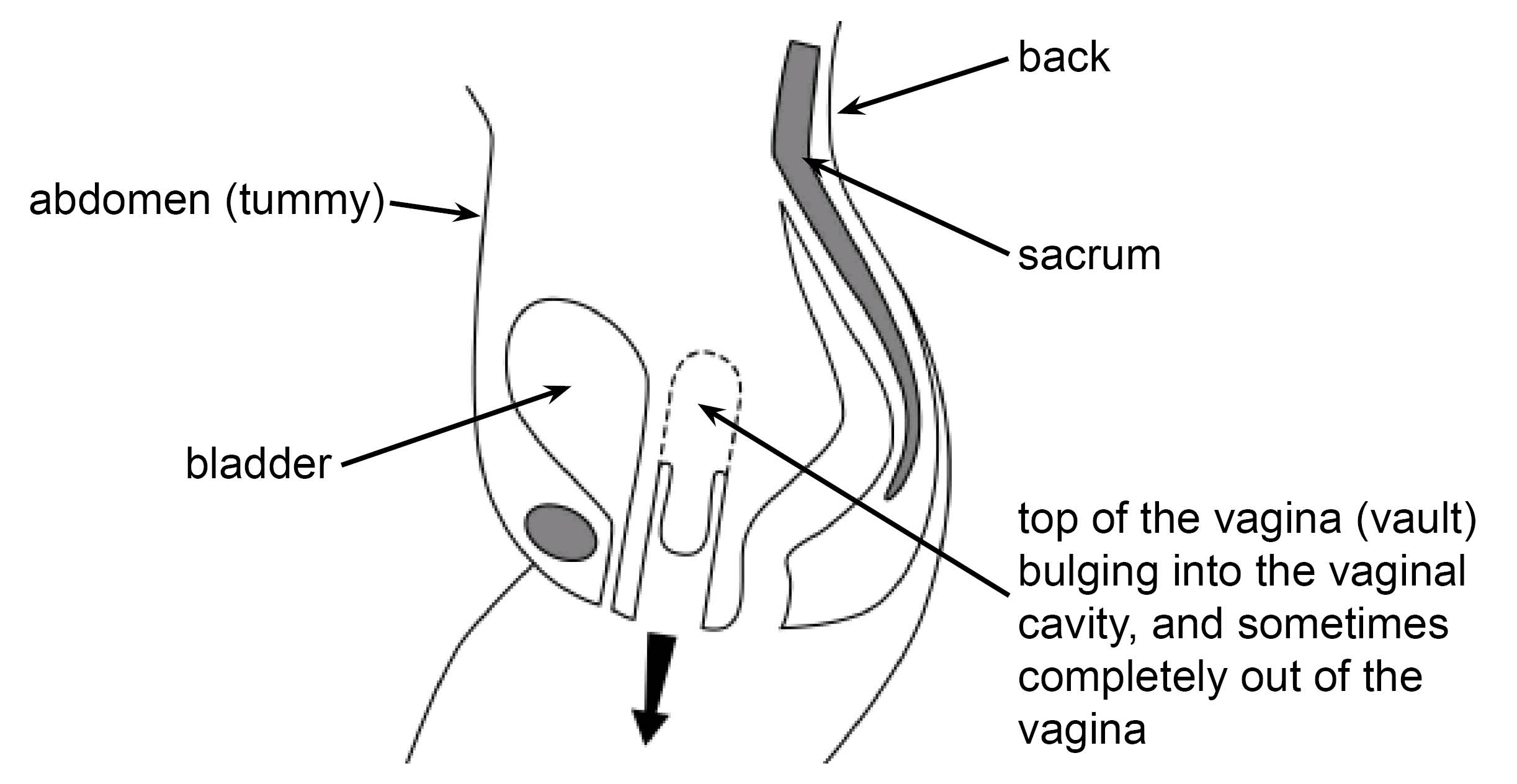

A prolapse is where the vaginal tissue is weak and bulges downwards into the vagina itself. In severe cases it can even protrude outside your vagina.

The apex is the deepest part of your vagina (top of it) where your uterus (womb) is usually found. If you have had a hysterectomy, the term ‘vault’ describes the area where your womb would have been attached to the top of your vagina (front passage). A vaginal vault prolapse is a prolapse arising from the vaginal vault.

A prolapse of the vaginal apex, is often accompanied by a posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Either:

a high posterior vaginal wall prolapse called a Enterocele; or

a low posterior vaginal wall prolapse called a Rectocele; or

sometimes both.

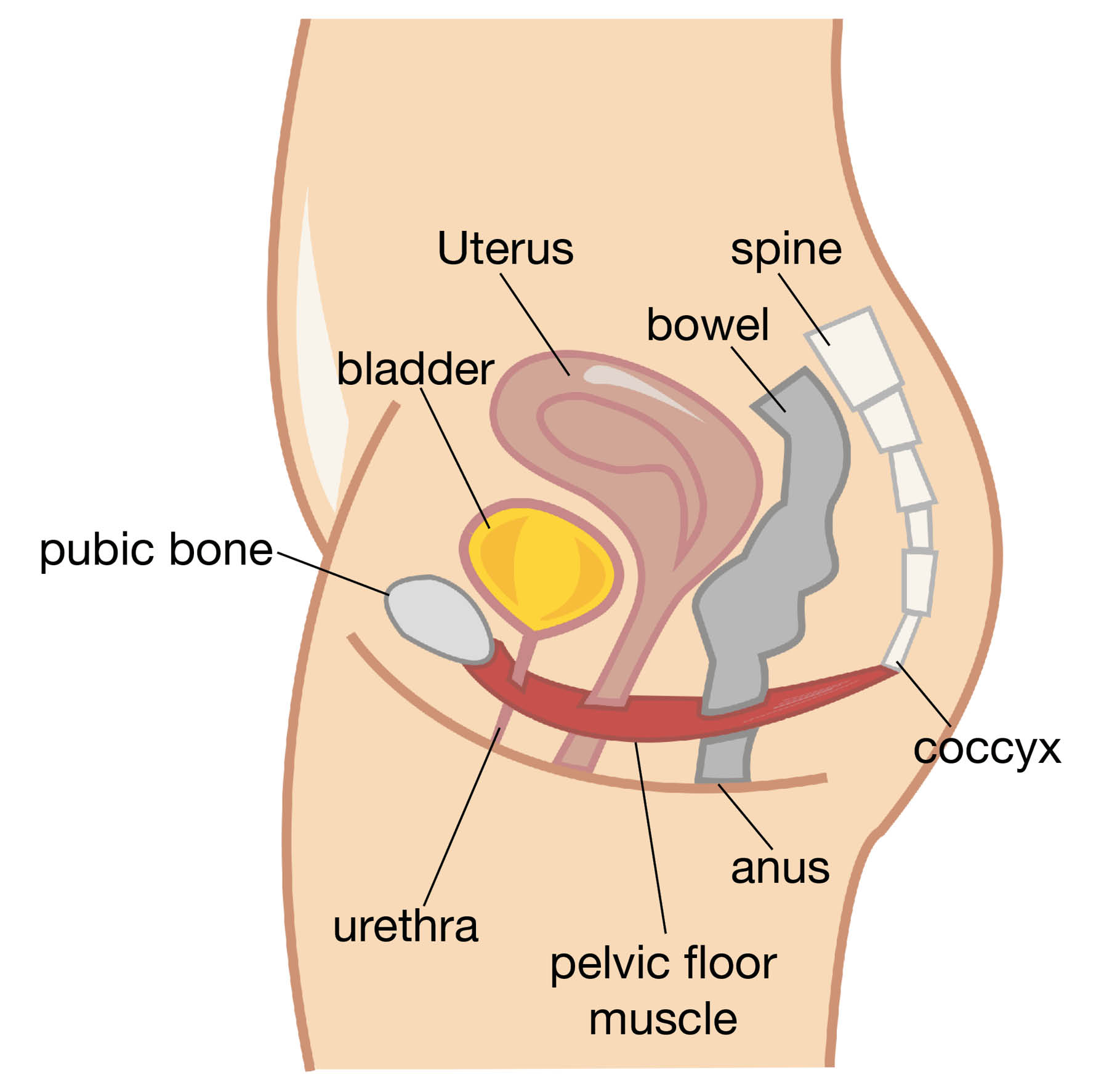

The pelvic floor muscles are a series of muscles that form a sling or hammock across the opening of your pelvis. These muscles and their surrounding tissue, keep your pelvic organs in place and working. Pelvic organs include the bladder, uterus, and rectum.

Prolapse happens when your pelvic floor muscles or vagina become weak. This is usually after childbirth. You will notice it most after menopause, when the quality of your supporting tissue weakens.

When straining, for example when going to the toilet, the weakness described above allows the:

vault of your vagina to bulge downwards; and

your rectum (back passage) to bulge into your vagina, and sometimes bulge out of your vagina.

When going to the toilet, some patients have to push the bulge back into their vagina with their fingers.

Occasionally, you may find that the bulge causes a dragging or aching sensation.

Are there alternatives to surgery?

Do nothing

If the prolapse (bulge) is not distressing, you may not need treatment. However, the prolapse may become dried-out and ulcerate, if:

it protrudes through the opening to your vagina; and

is exposed to the air.

Even if it is not causing symptoms, in this situation it is probably best to push it back with a ring pessary or have an operation to repair it.

Pelvic floor exercises (PFE)

The pelvic floor muscle runs from your coccyx at the back to your pubic bone at the front and off to the sides. This muscle supports your pelvic organs (uterus, vagina, bladder, and rectum). Any muscle in the body needs exercise to keep it strong, so that it works properly. This is more important if that muscle has been damaged.

PFE can strengthen your pelvic floor and give more support to your pelvic organs. These exercises may not get rid of your prolapse but they make you more comfortable.

PFE are best taught by an expert, who is usually a physiotherapist. These exercises have little or no risk. Even if you need surgery at a later date, they will help your overall chance of being more comfortable.

What are the different types of pessary?

Ring pessary is a soft plastic ring or device, which is inserted into the vagina and pushes the prolapse back up. This usually gets rid of the dragging sensation. It can also improve urinary and bowel symptoms.

A ring pessary needs to be changed every 4 to 6 months and is commonly used. We can show you an example in clinic. Some couples feel that the pessary gets in the way during sex, but many couples are not bothered by it.

Shelf pessary or Gellhorn. If you are not sexually active, this is a stronger pessary. It is inserted into your vagina, and needs changing every 4 to 6 months.

What are the general risks to having surgery?

Anaesthetic risk is very small, unless you have specific medical problems. This will be discussed with you before your surgery.

Haemorrhage. There is a risk of bleeding with any operation. The risk from blood loss is reduced by knowing your blood group and having blood available to give you if needed during surgery. It is rare that we have to transfuse patients after their operation.

There is a risk of infection at any of the wound sites. A significant infection is rare. The risk of infection is reduced, as we routinely give antibiotics to patients having major surgery.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a clot in the deep veins of the leg. Four to 5 in every 100 patients will develop a DVT, although most of these are without symptoms. Occasionally a DVT can move to the lungs, which can be very serious. In rare cases it can be fatal (less than 1 in 100 of those who get a clot).

A DVT can occur more often with major operations around the pelvis. The risk increases if you:

are obese (very overweight)

have gross varicose veins

have an infection

are immobile (not able to move around); or

you have other medical problems.

The risk is significantly reduced by using special stockings and having injections to thin the blood.

What are the specific risks of this surgery?

One in 4 patients may have short-term buttock pain. Long-term buttock pain occurs in around 1 in every 100 patients.

Damage to local organs. Local organs include the bowel, bladder, ureters (pipes from kidneys to the bladder), and blood vessels. This is a rare complication. If this happens, your surgeon will need to repair the damaged organ, which can result in a delay to your recovery.

If your bladder is opened during surgery, you will need a catheter for 7 to 14 days following surgery.

If your rectum (back passage) is damaged during surgery, this will be repaired. You may need another operation, and in rare cases, a temporary colostomy (bag).

Damage is sometimes not noticed at the time of surgery, so you may need to return to theatre.

Recurring prolapse. If you have one prolapse, 3 in 10 patients are at risk of having another prolapse during their lifetime. This is because their vaginal tissue is weak.

Painful sex. Once the wound at the top of your vagina has healed, there is nothing to stop you from having sex. The healing usually takes about 6 weeks. Some patients find sex uncomfortable at first. However, it gets better with time, and sometimes improves by using extra lubrication. Sometimes sex continues to be painful after the healing has finished, but this is unusual.

Change in sensation during sex. Sometimes the sensation during sex may be less, and orgasms may be less intense.

This operation has been performed for a long time. The success rate of the operation is 70 to 90%, this may go down with time. You should feel more comfortable following your operation. The sensation of the prolapse or something coming down, should have gone.

What happens before my operation?

Take the medication to soften your stools for at least 3 days before your operation. This will help to reduce your risk of getting constipated after your operation. Constipation is not pooing as often or finding it hard to poo. Taking the medication could also mean that you get to go home earlier. You can use Magnesium Sulphate, Lactulose, or Movicol. These medications are all available from your GP.

How is the sacrospinous fixation performed?

The operation can be done with a spinal or general anaesthetic, and you may have a choice in this.

A spinal anaesthetic involves an injection in the lower back, like what is used during labour or for a caesarean birth. The spinal anaesthetic numbs you from the waist down. It removes any sharp sensation, but you will still feel pressure during surgery.

A general anaesthetic is where you are asleep during the entire procedure.

Your legs are placed in stirrups (supported in the air).

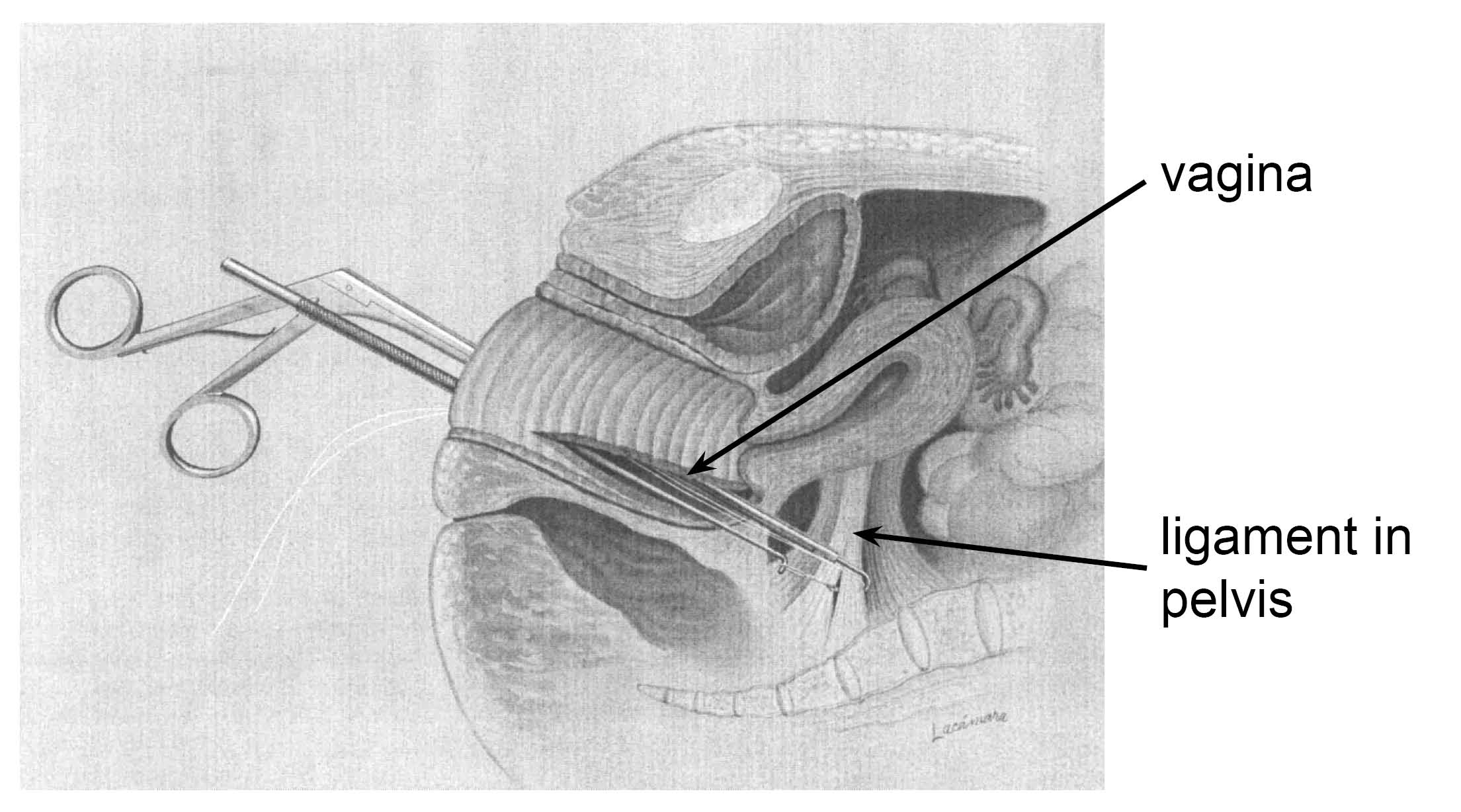

The operation is done through your vagina with special instruments (see diagram below).

The top of your vagina (if you have had a hysterectomy) or the neck of your womb (cervix) is suspended to a ligament in your pelvis called the sacrospinous ligament. This is done using suture (stitch) material that either:

dissolves slowly, over 3 months; or

is permanent.

Posterior repair may be done at the same time. For more information, ask a member of staff for a copy of the leaflet Posterior Vaginal Wall Repair without the use of mesh.

What happens after my operation?

When you return from the operating theatre, you will have a fine tube (drip) in one of your arm veins. Fluid will run through the drip to stop you getting dehydrated.

You may have a bandage in your vagina, called a ‘pack’ and a sanitary pad in place. This is to apply pressure to the wound, to stop it oozing.

You may have a tube (catheter) draining your bladder overnight. The catheter may give you the feeling that you need to pass urine, but this is not the case.

Usually the drip, pack, and catheter come out the morning after your surgery, or sometimes later the same day. This is not generally painful.

The day after your operation you will be encouraged to get out of bed and take short walks around the ward. This improves your general wellbeing, and reduces the risk of developing clots in your legs.

After the catheter is removed, the amount of urine you pass is measured the first couple of times you urinate (pee). An ultrasound scan of your bladder may be done on the ward, to make sure that you are emptying your bladder properly. If you leave a significant amount of urine in your bladder, the catheter may be re-inserted into your bladder for a couple more days.

You may be given injections to keep your blood thin and reduce the risk of blood clots. The injections are normally given once a day until you go home, or longer in some cases.

The wound is not normally very painful. However, sometimes you may need tablets or injections for pain relief. Please tell your nurse if you need extra pain relief.

There will be slight vaginal bleeding, like the end of a period. This may last for a few weeks.

The nurses will speak to you about sick notes and certificates. You are usually in hospital for up to 2 days.

What happens when I return home?

Moving around is very important. Using your leg muscles will reduce the risk of clots in the back of your legs (DVT), which can be very dangerous.

You are likely to feel tired. You may need to rest in the day from time to time for a month or more, but this will gradually improve.

It is important to avoid stretching the repair, particularly in the first weeks after surgery. Avoid constipation and heavy lifting. Drink plenty of water / juice, and eat fruit, green vegetables (especially broccoli), and plenty of roughage (such as bran and oats).

To avoid infection, do not use tampons for 6 weeks.

When will I have my stitches removed?

There are stitches in the skin wound in your vagina.

The parts of the stitches under the skin will melt away by themselves.

The surface knots of the stitches may appear on your underwear or pads after about 2 weeks. This is normal.

There may be a little bleeding again after about 2 weeks, when the surface knots fall off. This is normal and nothing to worry about.

When can I resume normal activities?

At 6 weeks gradually build-up your level of activity.

After 3 months, you should be able to return to your usual level of activity.

You should be able to return to a light job after about 6 weeks. Leave a very heavy or busy job until 12 weeks.

You can drive as soon as you are able to make an emergency stop without discomfort. This is usually after 3 weeks, but you must check this with your insurance company. Some insurance companies insist that you wait for 6 weeks.

After 6 weeks, you can have sex whenever you feel comfortable, as long as you have no blood loss. You will need to be gentle. You may wish to use lubrication, as some of the internal knots could cause your partner discomfort. You may wish to avoid sex until all the stitches have dissolved, typically 3 to 4 months.

Will I have a follow-up appointment?

If you need a follow-up appointment, this will be made for around 6 to 8 weeks after your operation. This appointment will be at the hospital (doctor or nurse), with your GP, or by telephone. Sometimes a follow-up appointment is not needed.

What if I have questions or concerns once I return home?

Contact the medical team or ward if there are any immediate problems after you return home. If you have any concerns in the days and weeks that follow, please contact your GP.

Further information

Bladder and Bowel Community

Nurse helpline for medical advice: 08453 450165

Counsellor helpline: 08707 703246

General enquiries: 01536 533255

Email

Ask 3 Questions

There may be choices to make about your healthcare. Before making any decisions, make sure you get the answers to these three questions:

What are my choices?

What is good and bad about each choice?

How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

Your healthcare team needs you to tell them what is important to you. It’s all about shared decision making.

What do you think of this leaflet?

We welcome feedback, whether positive or negative, as it helps us to improve our care and services.

If you would like to give us feedback about this leaflet, please fill in our short online survey. Either scan the QR code below, or use the web link. We do not record your personal information, unless you provide contact details and would like to talk to us some more.

If you would rather talk to someone instead of filling in a survey, please call the Patient Voice Team.

Patient Voice Team

Telephone: 01227 868605

Email