Dupuytren's disease

Information for patients from the Orthopaedic Hand Service

This leaflet provides general information about Dupuytren’s disease (also called Dupuytren’s contracture) including the treatment options available. It is not a substitute for your doctor’s advice.

What is Dupuytren’s disease?

Dupuytren’s disease is a condition that affects the hands and fingers, pronounced “doo-pwee-tranhz”. It is named after the French surgeon Baron Guillaume Dupuytren, who first described and researched the condition in 1834.

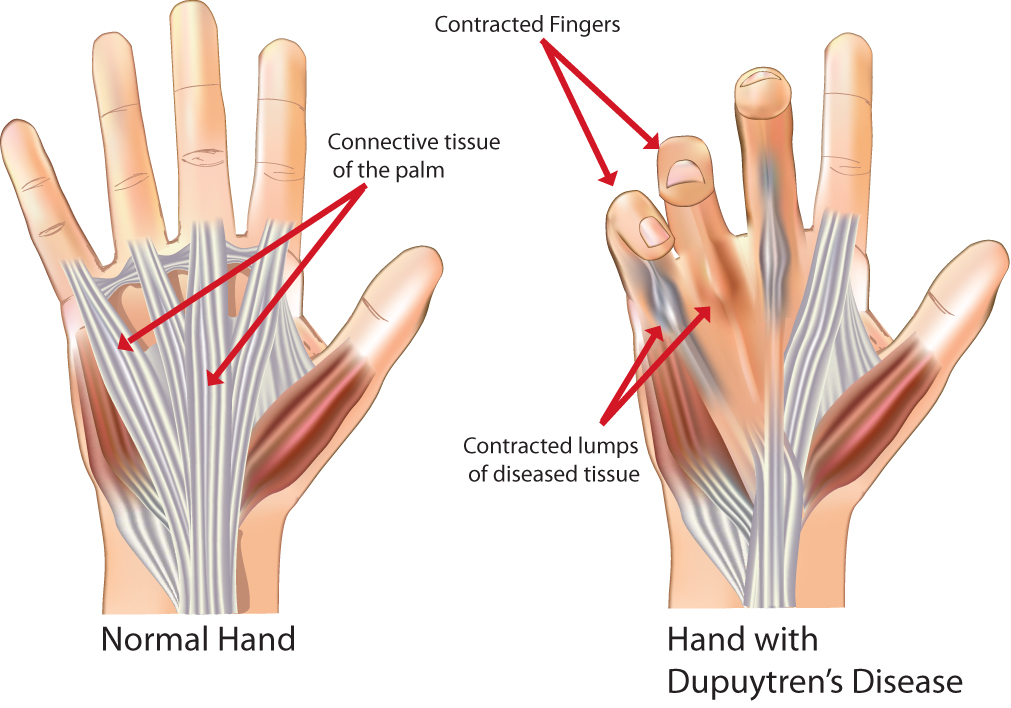

Dupuytren’s disease happens when a small lump of tissue develops in the connective tissue of the palm, usually where your ring and small fingers meet. Over time the lump can develop into a fibrous rope like cord connecting your palm to one or more of your fingers. As this happens your finger is pulled down making it difficult to fully straighten (known as a Dupuytren’s contracture). It most commonly affects the little and ring fingers, but can affect any fingers and can develop in both hands.

Dupuytren’s disease does not usually cause pain. When pain does occur, it is often early in the disease.

It is not a life threatening condition, but can cause problems if you try to do such things as putting your hand into a pocket or putting gloves on.

Symptoms are often mild and do not need treatment. However if it does get worse over time, treatment can be offered.

How common is Dupuytren’s disease?

Dupuytren’s disease is a fairly common condition. It tends to affect more men than women, and often happens in later life. It can affect up to two in every 10 men who are over 60 years of age, and two in every 10 women who are over 80 years of age.

Dupuytren’s disease is most commonly found in white Europeans, and mainly runs in families. Some other factors, such as heavy drinking, smoking, and diabetes, have been linked to the condition but the exact cause is still unknown. In most people with Dupuytren’s disease there is no known cause or linked illness or injury. It is not due to your type of job, vibrating tools, manual work, or other working environments.

How is Dupuytren’s disease diagnosed?

Dupuytren’s disease may be difficult to diagnose in its early stages. Most people do not see a health professional until the disease has progressed. A medical history and physical examination usually provide enough information for your health professional to diagnose whether you have Dupuytren’s disease.

How is it treated?

Many people with Dupuytren’s disease do not need any treatment. In many cases the condition remains mild and causes little interference with the use of their hand. There may be just thickened tissue, or thickened tissue with a mild contracture. In these cases, no treatment is usually advised.

There is no evidence to show exercise, splinting, or medications have any benefit on reducing the development of a contracture.

Will I need surgery?

Surgical treatment is needed only if the normal workings of your hand are affected, or are likely to become affected soon. The goal of surgery for Dupuytren’s contracture is to maintain or restore hand function by relieving the contracture in your fingers. However surgery is still not a cure for the disease, recurrence of Dupuytren’s disease is common but this may take many years.

What surgery is available?

There are several surgeries available that vary in complexity and complications. Your choice of procedure depends on the presentation of the disease in each of your hands.

Fasciectomy

A partial fasciectomy is the most common surgical procedure carried out for Dupuytren’s contracture in East Kent. It involves the removal of the abnormally thick and fibrous tissue in your palm and along your fingers, through a ‘zig zag’ cut. If your palm skin has become stuck (adhered) to the abnormal tissue, the skin may be removed along with the tissue and you will have a small skin graft (a dermofasciectomy). Surgery usually provides relief from contracture and allows you to move your fingers again.

The operation is carried out in the Day Surgery Unit. The operation is usually performed while you are awake using a regional anaesthetic, numbing only the arm affected. In some cases you may be given a general anaesthetic, where you are asleep for the operation. Local anaesthetic is often injected around the cut at the end of the operation; this may mean that the area and possibly some of your fingers will remain numb for many hours after your surgery.

Needle aponeurotomy

Needle aponeurotomy involves your surgeon pushing a fine needle through your skin, over the contracted cord. The sharp bevel of the needle is used to cut the thickened tissue under your skin.

This procedure is done under local anaesthetic (the area is numbed but you are awake). It is more likely that Dupuytren’s will return following a needle aponeurotomy, and patients having this treatment will be selected carefully to get the best outcome.

Needle aponeurotomy can be suitable for older patients who are unsuitable for surgery; or if the contracture is only affecting the knuckle joint. You will be advised if it is an option for you.

What are the risks and possible complications from surgery?

As with any surgery complications can happen, but with Dupuytren’s contracture they tend to be relatively mild. For needle aponeurotomy, the complication rate is low (around one in every 100 patients). Studies have found complication rates are higher with fasciectomy (around five in every 100 patients).

Complications can include.

It may not be possible to fully straighten your finger, particularly if your finger has been bent for a number of years.

Delayed wound healing or infection. A small number of patients will develop an infection after surgery, and may need antibiotics or a wash out procedure (more common in patients with diabetes).

Compared to non-smokers, smokers are more likely to have complications in tissue healing and infections after injuries or surgery. For free friendly support and medication to help you stop smoking, contact One You Kent on telephone 03001 231 220, or email.

Collection of blood or blood clots in the hand tissues (haematoma). This may need a second surgical procedure to remove the blood clot.

Damage to the skin, which results from trying to surgically separate the skin from the diseased tissue. It may take a little longer for the wound to heal, or the patient may need a skin graft during their procedure.

Dupuytren’s is a disease that can come back and also affect other fingers. Most patients will not need further surgery to an operated finger.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a rare condition but can cause severe pain, swelling, and stiffness in the hand which can take several months to improve or may even continue. Despite the list of complications and risks, please remember that most patients have an uncomplicated routine operation with very satisfactory recovery and outcome.

How do I care for my hand after surgery?

After surgery, your hand will be bandaged with a well-padded dressing which you must keep dry.

It is important to keep your hand elevated (raised) as much as possible to reduce the swelling.

You may have dissolvable stitches, or ones which will need to be removed between 10 to 14 days after surgery either by your GP, therapist, or consultant. This will be discussed with you when you have your surgery.

You should keep your surgical dressings in place until your first therapy appointment.

Will I need a follow-up appointment?

Yes, you will need a follow-up appointment with the Orthopaedic Hand Service around three to seven days after your surgery. At this appointment the therapists will remove your dressings and check your wound.

You will be given exercises and a removable splint to protect your hand (see image). This is likely to be worn during the day time for about two weeks and at night for several months after surgery. Some simple needle aponeurotomy procedures may not need you to wear a splint but this will be assessed by your therapist.

If you have had a dermofasciectomy, your therapy will not begin until seven to 14 days after your surgery.

Therapy may be needed for at least six weeks, depending on how quickly your wound heals and how quickly the normal movement in your hand returns. It is important to remember that your therapist is only there to guide you; it is up to you to do most of the work.

How soon after surgery can I drive?

You can start driving as soon as you feel confident enough to control your car safely and you are no longer wearing the splint during the day. This is usually about two to three weeks after surgery.

When can I return to work?

Return to work depends on the type of work you do. Someone who does heavy manual work may not be able to return for six weeks after having a skin graft. An office worker may be able to return to light duties a few days after having surgery. The same applies to sport and the type of sport you play. For advice, please speak to your consultant or therapist.

Further information

If you have any questions regarding your diagnosis or surgery, please contact your consultant or therapist. Further information can be found on the NHS web site.